Ancient Script

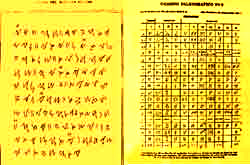

The most interesting paleographic peculiarity of Philippine scripts is its being traditionally written from bottom to top, with the succeeding lines following on the right.

The most interesting paleographic peculiarity of Philippine scripts is its being traditionally written from bottom to top, with the succeeding lines following on the right.

However, when the Spaniards attempted to use the script in their desire to spread the Christian Faith (like printing the Doctrina Cristiana in the Tagalog language and script), the direction of writing was changed and consequently the axis of the symbols also changed.

Introduction

One of the most spectacular events in the development of civilization is perhaps the invention of writing. To this, the Egyptians contributed their hieroglyphic writings, the Assyrians their cuneiform, the ancient Indians the brahmi and the Chinese their ideo-grammatic symbols.

The Easter Islanders of the mid-Pacific and the Mohenjorado and Harappa copies in Northwest India (now in Pakistan) also had their share in increasing man's cultural wealth by contributing their pictographic systems of writing. Not to be outdone were the people of Southeast Asia, who, though adapting an already developed system from India, also shared in further giving permanence to their thoughts and culture.

In ancient times the Philippines, as a member of this group of islands, developed a system of writing late in its proto-history, which contributed to the enrichment of its relatively limited cultural world. Studies on the Southeast Asian, particularly the Indonesian systems of writing, indicate they are derived from the South Indian development of the Brahmi Scripts used in the Asoka Inscriptions about 300 years B.C.

The Philippine scripts are related to the Southeast Asian systems of writing. This South Indian development is known as Pallava Grantha, a type of writing used in the writing of palm leaf books (called grantha) during the ascendancy of the Pallava dynasty about the fifth century A.D.

Theories in development & introduction of Philippine Scripts

At least six theories had been advanced on the development and introduction of Philippine scripts. Isaac Taylor sought to show that the system of writing, particularly the Tagalog, was introduced into the Philippines from the Coast of Bengal sometime before the eighth century A.D. In attempting to show such relationship, Taylor presented graphic representations of Kistna and Assam letters (like g, k, ng, t, m, h, and u) which resemble the same letters in Tagalog.

Fletcher Gardner argued that Philippine scripts have "very great similarity" with the Asoka alphabets. Gardner's view was somehow anticipated by T.H. Pardo de Tavera who wrote that "the Filipino alphabets have similarities with the characters of the Asokan inscriptions." David Diringer accepting the view that the alphabets of the Indonesian archipelago have their origins from India, opined that these, particularly that which is used in the Ci-Aruton inscriptions of the West Javan raja, King Purnavarman, constituted the earliest types of Philippine syllabic writing. These according to Diringer were brought to the Islands through the Buginese characters. The script would fall within the middle of the fifth century A.D. "

The Dravidian influence on the ancient Filipino scripts was obviously of Tamil origin," wrote V.A. Makarenko, in advancing another view on the origin of Philippine scripts. Based primarily on the work of H. Otiey Beyer, this theory argues that these scripts reached the Philippines via the last of the "six waves of migration that passed through the Philippine archipelago from the Asian continent . . . (about) . . . 200 B.C. . . .," constituting the Malayans and Dravidians, "primarily the Tamil from Malaya and the adjacent territories and from Indonesia and South India as well."

PECULIARITY

The most interesting paleographic peculiarity of Philippine scripts is its being traditionally written from bottom to top, with the succeeding lines following on the right. However, when the Spaniards attempted to use the script in their desire to spread the Christian Faith (like printing the Doctrina Cristiana in the Tagalog language and script), the direction of writing was changed and consequently the axis of the symbols also changed. These changes may be described in brief: the direction of writing proceeded from left to right, with the succeeding lines written below the previous line; while the axis of the symbols was rotated to a ninety degree position, in which the symbols for i and u in composition with any consonant became above and below, respectively. In the traditional position, the i and u were on the right and left, respectively, of the consonant with which they are composed.

Features

In general, the observable features of Philippine script may be categorized into two: (1) the curvi-linear character, and (2) the lineo-angular trait. To the first category belong the Tagbanwa, the Tagalog, Iloko, and all the other variants of lloko and Tagalog. The only example that may be cited under the second category is the Mangyan script. The scripts found in the Samar-Leyte area as reported by Alzina straddle the two categories-they show both lineo-angular and curvi-linear features. The general features of Philippine scripts previously described also apply to those that were in the Calatagan Pot; and the dating of the introduction of the system of writing into the Islands took into consideration the date of the Pot. In so far as archaeological evidence of the existence of writing in the Philippines is concerned, the inscribed Calatagan Pot is the only artifact that has been found. A number of archaeological reports of inscriptions from the direction of Batangas and Mindoro have been discovered on intensive study, to be fake. In the context of the Pot being the only artifact of this nature, it is, however, still difficult to accept as full archaeological evidence of the existence of writing in the proto-historic Philippines. We can only speculate on its authenticity. The successful decipherment of the inscription would open many 'dark rooms' in Philippine pre- and proto-history. For instance, the symbols will thus have been fully identified and show the various forms of the letters as they were known and used in prehistoric times. When this is successfully done, perhaps palaeographists would be able to give a better typological analysis of Philippine scripts. Furthermore, the decipherment of this inscription would also open to linguistic scientists a new field of study in terms of the structure of the Tagalog or Mangyan language in Pre-Hispanic times. The Maragtas and other "documents" (e.g., the Pavon, the Pove-dano and Romualdez manuscripts) do not seem to fit into the discussion of Philippine scripts. But they are indeed relevant in view of the claim that the Maragtas had been originally written in the ancient script, and that the others are manuscripts of pre-Hispanic provenance. Studies on Philippine scripts are still going on, in view of so many problems. In general terms, this system of writing, which flourished in the past among our early ancestors, indicates the advance, which our civilization has taken. Despite more than 400 years of foreign domination, some of our people, particularly the Mangyan and the Tagbanwa, have preserved their system of writing to this day. They still use this system for writing their songs and love letters, in recording their debts and in writing their tales. Excerpts from Filipino Heritage, Vol. 3, pp.598-601,Lahing Pilipino Publishing, Inc.